My Miniature Era

Documenting the resurgence of miniaturization in contemporary art

Scale is an important visual cue for the human eye. It denotes the relative size of one thing to another: continents to maps, an arrangement of objects in a still life.

William H. Johnson, Still Life - Bottles, Jugs, Pitcher, 1938

Scale proffers the durability of an object’s essence no matter the size. We dwell in the big and small, lost to the ongoing sameness protruding from the relational quality of life. The self is subject to the body, the book to the cover, the individual to the collective, microcosm to macrocosm; all Matryoshka dolls within Matryoshka dolls.

bigger is better

This maxim doesn’t come from nowhere; were there to be a study on the frequency of certain comments in undergraduate art school education, I’m sure the suggestion to make something ‘bigger’ would come out on top. Bigger artworks pair distastefully with contemporary art’s theoretical turn. But the trend to 'supersize' paintings may have peaked in 2022, writes Kate Brown. In an article for artnet she assesses the economic and ecological underpinnings of the increased downsizing of art, focusing on the art world as a system.

Herein, however, I am more interested in smallness as an aesthetic strategy. I am mainly trend forecasting, and this can be read like a style column in a fashion magazine featuring the utmost art world Thumbelinas on the cusp of shifting the size differential in artmaking. Beyond what is fashionable in the art world, however, I am also interested in sketching the theoretical underpinnings of my future work. This essay is an extended and almost durational entry in the realm of studio notes, formally, an artists’ writing.

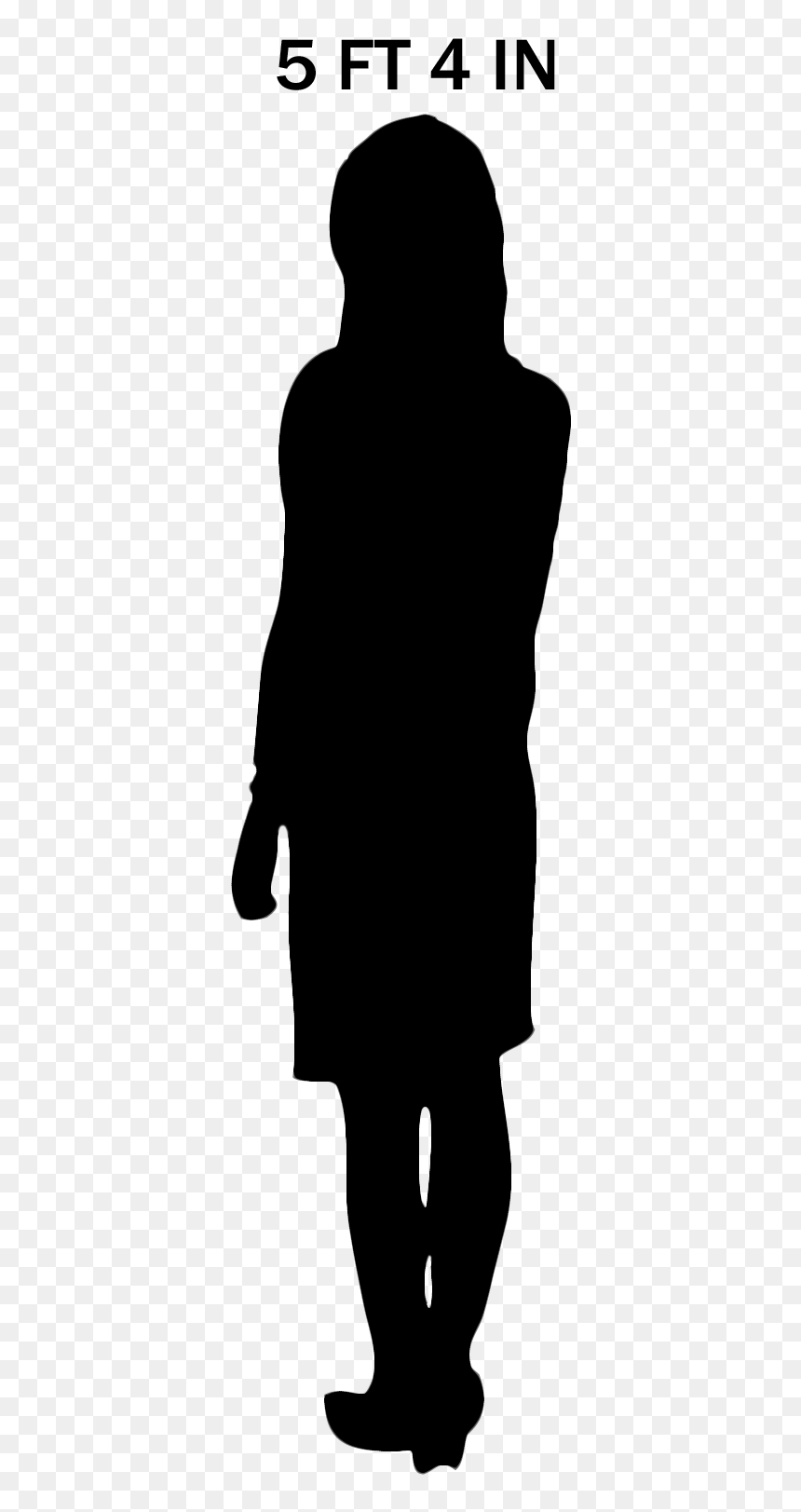

Miniature watercolors and paintings on glass from the 18th and 19th centuries. Credit: Bukowski’s

THE MEAT OF THE ISSUE

“craft always entails the making of actual things, not signs. The craft object is the thing itself.”

The appeal of the art object is its superfluity. It is always in excess of what it represents, best embodied by artistic intentionality, or a set of beliefs and ideas reflective of a creator. This excess is essentially the audience’s reaction or reading of the given artwork. The realm of interpretation.

I’m greatly familiar with the art vs. craft debate as a graduate of a textile arts department. Midway through, I realized that I could give a damn about craft and more readily identified as a painter. Craft, for me, is a means to an end. I traffic in the world of images, and what I create always points to something else which it is not. What artists call themselves is irrelevant: everything is a synonym for artist.

I am an appropriator, not a fabricator.

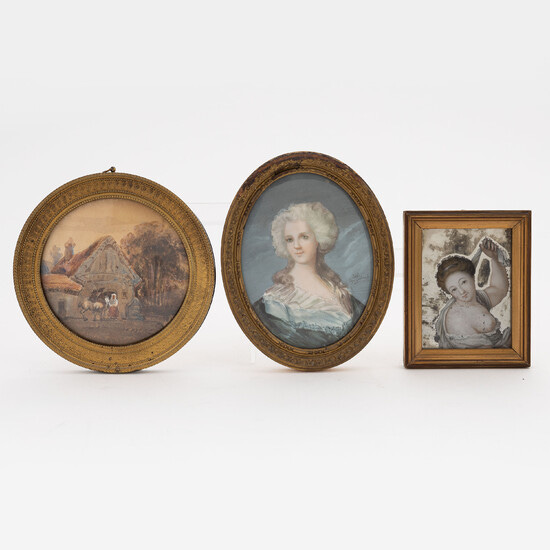

Ed Rossbach, Construction with Newspaper and Plastic Wall Hanging, 1968, Polyethylene film, twine, and newsprint

There is still much hand wringing to do about the difference between craft and art. On their part, artists working in the so-called intersection of craft and art attempt to elevate the former to the status of the latter by championing its labor-intensive qualities. For craft-oriented artists with this view, the amount of hours spent working on an embroidered tapestry thereby merits it as a work of art. Work, work, work, and bills, bills, bills! This point of view is best elucidated by historian Glenn Adamson’s writings on craft and subsequent texts on the connection between domesticity, minoritarian bodies, and traditional crafts including embroidery, pottery, quilting, sewing and weaving.

It’s not my intention to rehash the craft and art split in support of my expatriation from what is referred to in art school disciplinary nomenclature as “Material Studies.” But I do think that the notion of something being art because of how much time spent on it is fairly problematic. As artists, labor is a sticky situation wherein Marx’s alienation becomes ever so complicated. Additionally, how do we then account for artworks which belie time? I don’t mean to argue that the deskilled is better than the skilled, but that the craft vs. art debate ignores the fundamentally troubled relationship between the artist and her labor.

Contemporary art discourse has some allegiance to semiotics… but the craft vs. art debate is perhaps best elucidated by a distinction between sign and body. Racialization and gendering is perhaps the proliferation of the sign beyond the body. The notions of private and public are comparable to the sign and its object. In the public we traffic among a world of signs which mediate the body and the self’s inwardness. Discourse emits from the body’s publicness, an attempt to face interiority with exteriority. My sign-body floats before me, precedes me even. Relational, again.

i <3

her artistic condition came first to my own

the sun bleached her pill bottle

smeared blue-black ink along the reel of the dream

Water-damaged book

digression

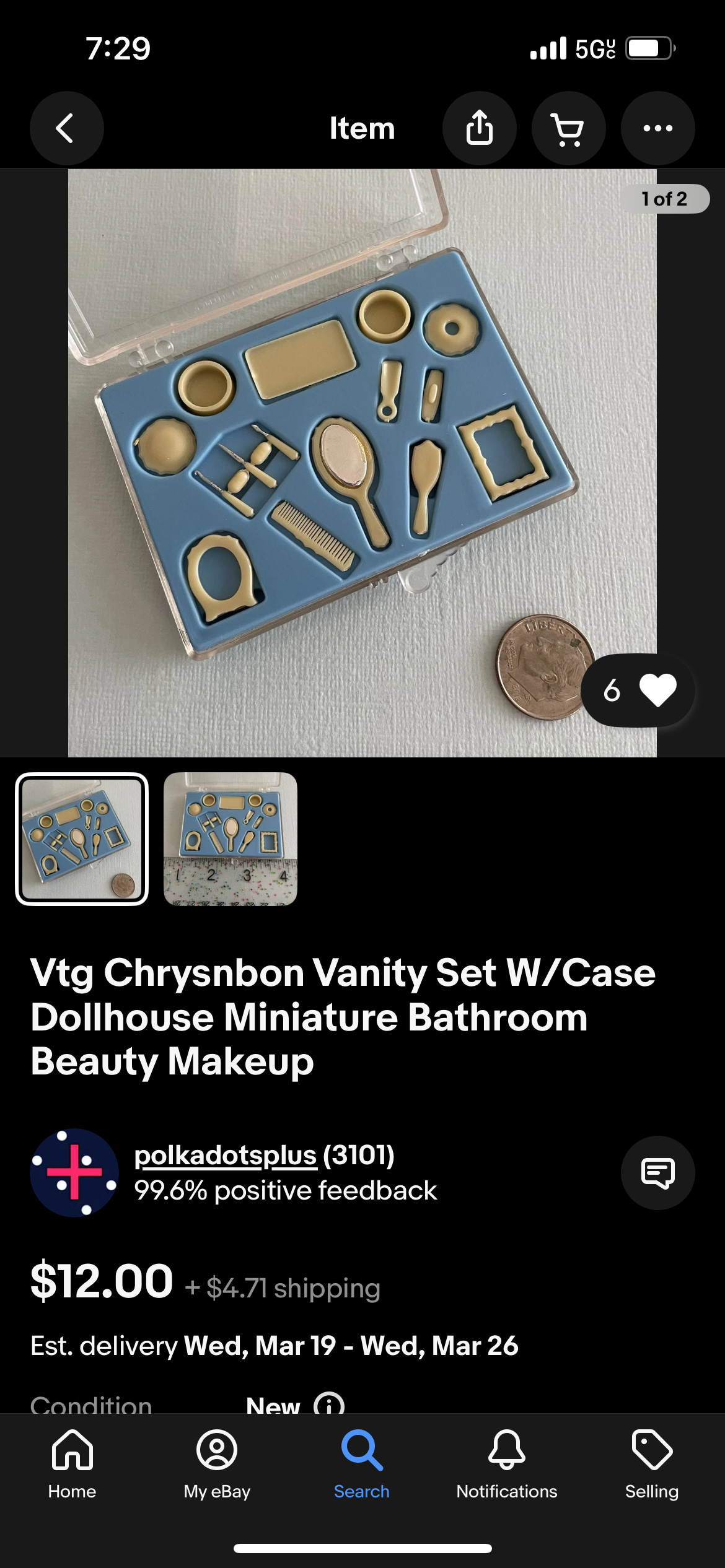

A dollhouse,

A diorama,

A miniature

Interiors reflecting interiors

Interiority facing a mirror produces many interiorities

Mirror phase

Projections on projections

The miniature creates a fantasy space

Enacting control, power

Where the creator feels none

girl art and its discontents (or maybe it’s just cute)

With the emergence of woman-dominated expressions of dollhouse craft, the classic semiotic relationship set out by Risatti (an art object –(referencing) → a craft object) becomes infinitely troubled. Early dollhouses were the domain of housewives, and like other traditional crafts, grew to assume a gendered dimension.

A dollhouse is an image pointing to another image.

i love the image of the sunset more than the sunset itself

Janet Olivia Henry, The Studio Visit, 1983, mixed-media installation.

I’m not interested in simulacra, but something more base and vulgar.

The history of miniatures isn’t completely girl art. Nevertheless, it’s impossible to ignore the gendered, or better put, abject dimensions of things becoming really small. Thumbelina’s small stature is figured as a deformity in the original fairytale, and Alice’s fluctuating size after she encounters Wonderland troubles her greatly. What is small, cute, picayune, is inevitably identified with femininity.

Animated stills from Alice in Wonderland (1951)

It’s perhaps a reach to align the preoccupation with size in modern fairy tales and children’s storybook media with the contemporary woman’s fascination with her diet. Like weight, size ultimately prefigures an issue with control and manageability. In the case of Thumbelina, her tiny stature is inborn. With Alice, she controls her size through the use of various magical potions.

The miniature enacts the fantasy of control.

Alice shrinks after drinking ‘The Drink Me Bottle’

The miniature is everything as it should be.

I would love you if you were perfect.

Images reflecting other images, mirrors on mirrors, pools of clear water.

arcadia

the miniature is like shopping forever

an ambient consumption

polka dot sound

i forget I’m shopping

i don’t know i’m a customer yet

utopia

Nothing is more utopic than a reflective surface: the reverse is things as it should be.

in analysis i feel the pleasure of the reflective gaze, like staring into pools of water or reading for long periods of time.

Thumbelina echoes the tale of Snow White; in both fairy tales, the heroine’s time with her mother in the beginning of the story can be described as a beatific mother-daughter paradise.

digression

Another use of Thumbelina: Michel Serres’ La Petite Poucette where he dubbed millennials as the ‘thumbelina generation.’ Serres’ Thumbelinas are able to navigate the miniature worlds of their phones with ease. Thumbelina after all is no bigger than a thumb, and the thumb becomes the main apparatus for interacting with the world in the third millennium.

You are most beautiful when you stare at the screen

The screen’s predecessor being the page

The page the mirror

The sequel to Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland: Through the Looking-Glass, where Alice climbs into a fantastical world through a mirror.

Women are the ultimate interiors. The preoccupation with the woman’s secret.

Love Streams (1984) dir. Cassavettes

An obsession with woman’s interiority produces the muse.

How my mother always described the ‘pocketbook’: mirrors reflecting mirrors, endless reflections, innerness upon innerness.

What’s her secret?

All writing comes from the well.

case studies

The Stettheimer Dollhouse complete with miniature (real) artworks

Carrie Stettheimer’s unfinished dollhouse received beaucoup attention in the twenty-tens via her more famous sister Florine’s portraits. There are few in-depth studies dedicated to the Stettheimer dollhouse, though Quinn Darlington’s “Modernism’s Miniatures” is notable in its attempt to locate dollhouses as one of modernism’s discontents. Darlington on Stettheimer: “...it would seem that she ultimately preferred “living” in the Dollhouse herself…” (Darlington 62) Again, the male element is completely lacking. Or is it?

Florine Stettheimer, Costume design (Androcles and the Lion) for artist's ballet Orphée of the Quat-z-arts, c.1912 Oil, yarn, fabric, and lace on wood

Stettheimer’s dollhouse was a collaborative effort: she commisioned her artist friends to submit miniature works, most notably Marcel Duchamp’s contribution of a pen-and-pencil version of Nude Descending A Staircase in 1912.

Duchamp’s miniature edition of Nude predates his work La Boite-en-Valise by two years and Stettheimer’s influence on the former artist’s work is notable. Carrie Stettheimer is a hidden muse in Duchamp’s oeuvre.

Godard’s maquettes for the Centre Pompidou completed in 2005 are another celebrated entry in the genre of male miniatures. Thinking alongside Risatti, however, they ultimately point outwards, serving as thwarted models for the retrospective Godard had at Pompidou. This is the crux of the male miniature (dioramas, model cars): it exhibits something. The exhibition itself as a mini-museum.

Again Darlington: it would seem that she ultimately preferred “living” in the Dollhouse itself.

That is, the dollhouse is multidirectional: refracting rays of the mirror lead back to the source, the infinite reflections of the dollhouse’s light.

Godard’s maquettes, Duchamp’s La Boite-en-Valise are both unidirectional. They point to one thing: the art object, the exhibition, the retrospective, the oeuvre. This is the classic semiotic relationship between the art object and the image charted by Risatti.

Documentation of Godard’s Voyage(s) en utopie by Michael Witt

To extend Risatti’s argument, perhaps the art and craft divide is not over semiotics but instead the ‘image.’ Artworks are images. The mirror-image being the first image beyond a child’s cheek. The weaving’s functionality is its mortality, the durational aspect of the craft object linked to its material existence. The extent of the art object is linked to the human impossession of the image. Thumbelina carries her phone filled with pictures. It is human to expect the photograph to outlast the photographed.

Catching butterflies but it’s impossible.

Let’s try to catch images instead.

1,2,3…

Thorne miniature rooms at the Art Institute of Chicago

ERRATA

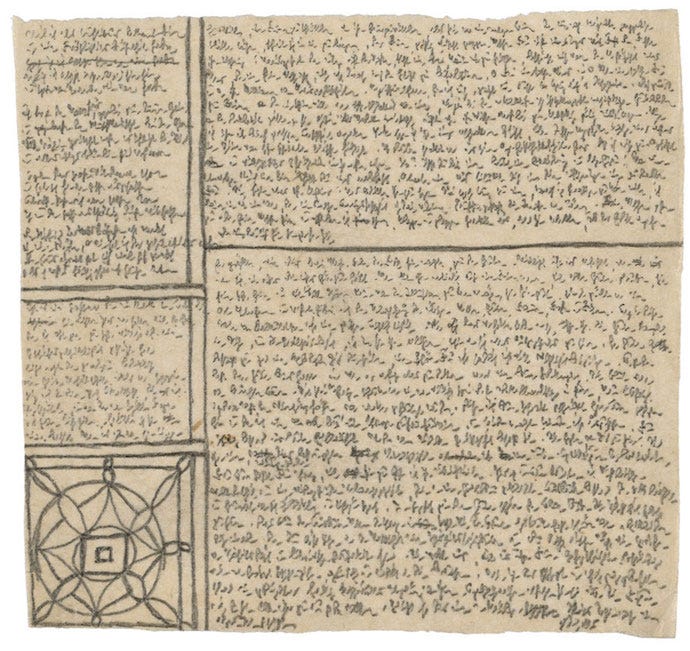

I’ve touched on miniaturization as a simultaneously renewed and emergent strategy in contemporary art, but its effects can be observed in other media. Not quite contemporary, Robert Walser’s ‘micro-scripts’ resound with the memetic capacity of miniatures. Walser’s tiny writings were done with pencil, a noticeable shift from early twentieth century writers’ penchant for the typewriter. Walser’s miniascule writings were completed in an archaic German script. The meaning-making potentiality of the micro-scripts lies in its plying of a sub-German within German, like nesting dolls.

An example of Robert Walser’s microgrammes

Walser’s microscripts present the writing as it should be: as a whole. Our main experience of writing occurs through seriality: page to page, exposition develops. Taken comprehensively, the writing transforms into a ‘simultaneous’ experience, imbibed by the body, not unlike painting, a Eucharist.

There is a passage of Saint Genet that often troubled me. Its meaning remained undisclosed despite conversations with erudite friends. Here, I will reproduce it in full:

“The phenomenon of saintliness appears chiefly in societies of consumers. A full description of such societies would be beyond the scope of the present work. I shall mention only a few of their features: they confuse the essence and the practical purpose of the manufactured object; work is not creative, it has no value in itself, it is the inessential mediation that the merchandise chooses in order to move from potentiality to the act; a simple-minded practicality stresses the final aspect of the product; the truth of its being appears when it is presented to the purchaser or user as a polished, varnished, sparkling object; it is then revealed as both a thing in the world and as an exigency; it demands, in its being, that it be consumed. The work is merely a preparation: servants dress the bride; consumption is a nuptial union; as a ritual destruction of the 'commodity"—instantaneous in the case of food products, slow and progressive in that of clothing and tools—it eternalizes the destroyed object, joins it in its essence and changes it into itself, and, at the same time, incorporates it symbolically into its owner in the form of a quality.” (Sartre 195-96)

What I think Sartre is referring to is a condition of society where saints interact as images on the lens of the human eye. The Catholic predilection for iconophilia poses an essential schism for Christians due to iconophilia’s fatal act: the reproduction of God. Protestant iconophobia is historically less popular but has maintained devoted adherents. Abrahamic religion becomes beautiful in its central crisis over the image. Image-worship is the central concern of artists, and the miniature is its most perfect manifestation. Artists can be classed into three types: iconophiles (lovers of images), iconlaters (worshippers of images), and iconoclasts (destroyers of images).

An incomplete list of artists and works in the miniature mode that weren’t mentioned in detail but were referenced for this writing: Hans Christian Anderson’s paper cuttings, Sam Anderson, Sophie Tauber Arp, Duo ASMA ASMA, Fatine-Violette Sabiri and Shahan Assadourian, Julie Becker, Beverly Buchanan, Joseph Cornell, Mark Dion, Elizabeth Englander, Faith****, Alix Ferrand, Ella Fleck, Sayre Gomez, Janet Olivia Henry, Mike Kelley , Win Mccarthy, Picasso’s maquettes, Thomas Rainy, Betye Saar, Curtis Talwst Santiago.

Brown, Kate. “Why Is Small Art So Big Right Now?” Artnet News, 22 Jan. 2025, https://news.artnet.com/art-world/small-art-2599293.

Burch, Robert. “Charles Sanders Peirce.” The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, edited by Edward N. Zalta and Uri Nodelman, Summer 2024, Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University, 2024. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2024/entries/peirce/.

Darlington, Quinn. Modernism’s Miniatures: Space and Gender in the Stettheimer Dollhouse and Duchamp’s Boîte-En-Valise. 2012. University of Notre Dame, thesis. curate.nd.edu, https://doi.org/10.7274/n296ww74n5t.

Heiner, Heidi, and Kathleen O’Neill. “SurLaLune Fairy Tales: Annotations for Thumbelina.” SurLaLune Fairy Tales, https://surlalunefairytales.com/oldsite/thumbelina/notes.html. Accessed 30 May 2025.

Risatti, Howard, and Kenneth R. Trapp. A Theory of Craft: Function and Aesthetic Expression. The University of North Carolina Press, 2013.

Sartre, Jean-Paul. Saint Genet. Pantheon, 1983.